Effective Game Killing - Part 2 By Nathan Foster

Putting the information together

The speed of incapacitation or what we call fast killing is one method for which the hunter is able to measure a cartridge's effectiveness on game in comparison to other cartridges. It must be remembered however that the word effective by definition in this instance describes the ability of the cartridge to achieve fast incapacitation and has no maximum limit to power. An efficient cartridge on the other hand describes the ability of the cartridge to kill using the minimum necessary power. I do not believe that efficiency should ever be put exclusively ahead of effectiveness (fast killing).

With regards to shot placement versus mechanical wounding, a good example of this can be found in the .243 Winchester. At ranges beyond 200 yards and especially at ranges of around 300 yards the .243 can produce slow kills with rear lung shots due to narrow wounding. By bringing shot placement forwards to the line of the foreleg or 1 to 2" further forwards of the line of the foreleg, a fast kill can be obtained via direct destruction of the autonomic plexus (nerve ganglia between the heart and lungs). If however, such shot placement cannot be guaranteed, a change to (for example) the .270 Winchester, will ensure greater internal wounding with rear lung shots, effecting a faster kill.

Shot placement, as just described with the .243, can of course negate the need for hydrostatic shock or immensely wide wounding as a result of hydraulic shock. An accurate but low velocity rifle/ cartridge combination capable of striking the autonomic plexus of game in a reliable manner will anchor game just as quickly as a cartridge capable of producing hydrostatic shock with rear lung shots. On the other hand, the hunter is not always presented with the perfect shot. Therefore, the more effective a cartridge is regarding wounding, the more forgiving it can be with less than ideal shot placement.

So far we have discussed Hydrostatic shock in great detail while only touching on hydraulic shock. Like Hydrostatic shock, hydraulic shock is increased at high velocities and has similar cut of points at different velocity parameters. Looking at one projectile as an example, the 130 grain .270 Winchester Interbond expands to a diameter of between 13 and 17mm at high impact velocities. The wound channel this creates through vitals is around 50 to 75mm (2-3") in diameter. This is what I call disproportionate to caliber wounding and it is very effective. As velocity falls to 2600fps, wounding tapers off slightly, the internal wounds being around 25-40mm (1-1.5") in diameter.

As velocity falls below 2400fps, wounding gradually becomes proportionate to caliber, noticeably so at 2200fps. Between 2200fps and 2000fps (450 to 575 yards), the Interbond projectile expands to a diameter of around 8 to 9mm, creating a wound channel of around 8 to 9mm, resulting in slow bleeding and therefore, if the CNS is not destroyed, a very slow kill.

To regain disproportionate to caliber wounding at low velocities, the projectile must be capable of shedding a large amount of its bullet weight, up to 90%, allowing a cluster of fragments to create wide internal wounding to increase the speed of blood loss for fast killing. The term I use for this is "mechanical wounding" Here again my research deviates from the usual literature. And with the arms industry currently rushing to produce small low powered assault rifle cartridges that boast magical killing power, industry players are themselves having to more fully explore these subjects while terms like temporary wound channel lose even more of their sparkle.

Although bullet weight loss is critical for fast killing at low velocities, this does not mean to say that a .22-250 loaded with a varmint bullet will produce clean kills with chest shots on medium game. The cluster must also be matched to game body weights, having optimal density and momentum.

Although a frangible bullet is able to produce wide wounding due to mechanical destruction alone, hydraulic shock also occurs at much lower impact velocities than a controlled expanding bullet. As suggested earlier, Hornady research suggests that blood pressure spikes in the brain cause coma, resulting in (as much as possible) a painless death. Whether from a hydraulic or mechanical perspective, wounding of fragmentary bullets is much higher than that of controlled expanding bullets at low impact velocities, providing the cluster has sufficient density and momentum relative to game body weights.

During TBR testing, a packet of vintage Winchester Western .30-30 160 grain hollow point ammunition was tested on medium game animals. This is perhaps the earliest example of a frangible bullet. As best as could be determined after extensive research, it could be concluded that historically, the .30-30 was possibly not standing up to its design premise and that a frangible bullet was adopted to increase wounding capacity.

The .30-30 160 grain soft point load was intended to produce wide wounding and fast kills as a result of the newly discovered powders which generated exceptionally high velocities (for 1894). This was a complete turnaround from past terminal ballistics research which had proven that the bigger the bore, the wider the wound. The .30-30 (.30 WCF) loaded with a controlled expanding bullet is not a great deal more emphatic than the .45/70, the .45/70 having already proven to be an emphatic killer. Western's hollow point load was introduced a little while after the soft point.

While the frangible .30-30 bullet would have been acceptable for use on the smaller deer species of the U.S, one has to wonder how this load fared on the Grizzly bear featured on the ammunition box of the .30-30 hollow point ammunition. The results would most likely have been disastrous. About 200 grains is a safe minimum frangible bullet weight for these body weights.

Frangible bullets are important at low velocities, especially at long ranges. A frangible bullet capable of rendering a wide wound in the absence of disproportionate to caliber wounding (high velocity) helps ensure fast bleeding for fast killing.

As a short recap, with ideal shot placement and utilizing a cartridge with sufficient power to penetrate the vitals of intended game, we can destroy the CNS and cause an instant kill - however this is often idealistic and unrealistic. With less than ideal shot placement, high velocity can initiate hydrostatic shock and hydraulic wounding to help ensure fast kills out to ordinary hunting ranges (300 yards). In the absence of high velocity, a fragmentary projectile can ensure fast killing via hydraulic shock and wide (mechanical) wounding, producing fast bleeding. In all instances, bullet weight and bullet construction need to be matched to the job at hand.

Please try to remember the following for medium game hunting:

Choose light and stout or heavy and soft.

A light but stout projectile can deliver hydrostatic shock while having the tough bullet construction needed to deliver sufficient penetration. However this has a range limitation, usually of around 300 yards, after which, careful shot placement is required. This can be counterproductive in cross winds. Nevertheless, this method is often the most effective for minimizing meat damage on lighter medium game at ordinary hunting ranges (out to 300 yards).

When chest shooting heavy game, a heavy but stout controlled expanding projectile driven as fast as the shooter can manage produces the fastest possible killing. As O'Rourke said, use enough gun.

Use enough gun. The .338 Win Mag and controlled expanding 225gr Nosler Partition can be put to great work on bear. That said, shot placement is a key factor to effect extremely fast killing.

A heavy yet soft and frangible or partially frangible projectile (loses some weight) may not deliver hydrostatic shock very far depending on game body weights, but providing the cluster is dense enough, it will be capable of rendering deep, broad and highly traumatic wounding across a wide range of body weights. Good frangible bullet designs can continue to produce mechanical wounding and a measure of hydraulic shock down to impact velocities of 1600fps with some exceptional projectiles continuing to produce excellent performance down to velocities as low as 1400fps.

For those wondering about the middle ground between light and stout and heavy and soft, there are certainly some good bullet designs on the market. One of the best middle ground bullets is the Hornady SST, a semi frangible bullet design that tries to retain some weight for penetration. A specific example is the 7mm 162 grain SST which is effective on Red/Mule deer at close ranges (adequate penetration) yet is capable of producing wide wounding at extended ranges (around 1000 yards in the 7mm Remington Magnum).

On the other hand, we do have to be a bit careful with the middle ground. For example, the Nosler Accubond has core bonding in an attempt to toughen the bullet but is also designed to be fast expanding and is generally available in mid weights such as the 140 grain .270 Winchester bullet. This particular load works extremely well on mid-sized deer at ordinary hunting ranges however, the Accubond can suffer when pushed to the extremes. It can be too stout for low velocity work yet too soft for tough game. In this regard, we have to be careful as to how we use a 'general purpose' bullet design.

You may wish to take a note from the Taoists and choose the middle ground so as to be prepared for any contingency, however if you fail to fully understand the limits of your cartridge versus your intended game, you may choose something which is neither fish nor fowl and does a generally bad job within the role you have chosen for it. For example, you may load the .375 caliber 260 grain Accubond for an African trip. And while this works exceptionally well on some larger bodied game, you might be in for a world of hurt if you try to tackle a cape buffalo with this bullet and find that it completely runs out of steam before reaching vitals. Please use my cartridge knowledge base and books to obtain a deeper understanding of how each of the manufacturers bullets work, their strengths and limitations.

I have been continuously researching wounding for most of my life and the results and variables are far greater than can be covered in one short document on effective game killing. Nevertheless a rudimentary understanding of the fundamentals of game killing, wounding and speed of killing can serve as a useful platform before continuing on and exploring my in-depth research as well as your own field observations.

Looking forwards, we seem to be heading towards some very strange extremes. In one camp, we have hunters looking for any excuse to use low powered cartridges in short barreled suppressed rifles and or AR-15 platform rifles while in the other extreme, a few gun companies continue to work towards barrel destroying ultra-velocity magnums. Either approach can cause a great deal of problems for hunters. Ultra-fast cartridges can cause shallow penetration at close ranges and ironically still lead to disappointment when bullets still display vast drop and wind drift at truly long ranges. The fastest cartridges may have a barrel life of less than 600 rounds, 200 of which may be used up during load development.

Modern low powered cartridges are simply that - low in power. You do not have to be rocket scientist to figure this out. If the bullet is the same weight as a 7.62x39 or .30-30 bullet and going at the same speed, it will produce the same results regardless of how it is labelled. To recap from earlier, the slower you go - the wider you need to go (think .45 etc) or the more the bullet needs to shed weight if we are seeking optimum killing performance. This also ties back into the problem of forcing people to use homogenous copper bullets for environmental reasons. Low power and stout bullets simply don't work that well together unless the projectile has specialized design characteristics.

If the bullet is to shed weight it may need significant weight to begin with (depending on the size animals you are hunting) in order to achieve reliable penetration. Also remember this; there is little that can be done now that has not been done before. There is no new magical cartridge that offers twice the killing power with half the energy. Projectile designs are certainly advancing in some areas however there are limitations as to how far this can be taken.

As a hunter, the primary factor that must be foremost in your mind is animal welfare, not how short or light your rifle is or whether it can handle a thirty round magazine (even if you are a culler). Factors such as recoil or cost should also be treated as secondary to the primary goal of a fast effective kill.

As far as new cartridge designs go, please try to refrain from becoming caught up in hype. The physics of wounding are really rather straight forwards once you have a full understanding of the basics. The trick is just that - to understand the basics. Once you have understood the fundamentals of game killing and how cartridges behave in general, then you can move forwards and not be misled by marketing fabrications.

Putting the information together

The speed of incapacitation or what we call fast killing is one method for which the hunter is able to measure a cartridge's effectiveness on game in comparison to other cartridges. It must be remembered however that the word effective by definition in this instance describes the ability of the cartridge to achieve fast incapacitation and has no maximum limit to power. An efficient cartridge on the other hand describes the ability of the cartridge to kill using the minimum necessary power. I do not believe that efficiency should ever be put exclusively ahead of effectiveness (fast killing).

With regards to shot placement versus mechanical wounding, a good example of this can be found in the .243 Winchester. At ranges beyond 200 yards and especially at ranges of around 300 yards the .243 can produce slow kills with rear lung shots due to narrow wounding. By bringing shot placement forwards to the line of the foreleg or 1 to 2" further forwards of the line of the foreleg, a fast kill can be obtained via direct destruction of the autonomic plexus (nerve ganglia between the heart and lungs). If however, such shot placement cannot be guaranteed, a change to (for example) the .270 Winchester, will ensure greater internal wounding with rear lung shots, effecting a faster kill.

Shot placement, as just described with the .243, can of course negate the need for hydrostatic shock or immensely wide wounding as a result of hydraulic shock. An accurate but low velocity rifle/ cartridge combination capable of striking the autonomic plexus of game in a reliable manner will anchor game just as quickly as a cartridge capable of producing hydrostatic shock with rear lung shots. On the other hand, the hunter is not always presented with the perfect shot. Therefore, the more effective a cartridge is regarding wounding, the more forgiving it can be with less than ideal shot placement.

So far we have discussed Hydrostatic shock in great detail while only touching on hydraulic shock. Like Hydrostatic shock, hydraulic shock is increased at high velocities and has similar cut of points at different velocity parameters. Looking at one projectile as an example, the 130 grain .270 Winchester Interbond expands to a diameter of between 13 and 17mm at high impact velocities. The wound channel this creates through vitals is around 50 to 75mm (2-3") in diameter. This is what I call disproportionate to caliber wounding and it is very effective. As velocity falls to 2600fps, wounding tapers off slightly, the internal wounds being around 25-40mm (1-1.5") in diameter.

As velocity falls below 2400fps, wounding gradually becomes proportionate to caliber, noticeably so at 2200fps. Between 2200fps and 2000fps (450 to 575 yards), the Interbond projectile expands to a diameter of around 8 to 9mm, creating a wound channel of around 8 to 9mm, resulting in slow bleeding and therefore, if the CNS is not destroyed, a very slow kill.

To regain disproportionate to caliber wounding at low velocities, the projectile must be capable of shedding a large amount of its bullet weight, up to 90%, allowing a cluster of fragments to create wide internal wounding to increase the speed of blood loss for fast killing. The term I use for this is "mechanical wounding" Here again my research deviates from the usual literature. And with the arms industry currently rushing to produce small low powered assault rifle cartridges that boast magical killing power, industry players are themselves having to more fully explore these subjects while terms like temporary wound channel lose even more of their sparkle.

Although bullet weight loss is critical for fast killing at low velocities, this does not mean to say that a .22-250 loaded with a varmint bullet will produce clean kills with chest shots on medium game. The cluster must also be matched to game body weights, having optimal density and momentum.

Although a frangible bullet is able to produce wide wounding due to mechanical destruction alone, hydraulic shock also occurs at much lower impact velocities than a controlled expanding bullet. As suggested earlier, Hornady research suggests that blood pressure spikes in the brain cause coma, resulting in (as much as possible) a painless death. Whether from a hydraulic or mechanical perspective, wounding of fragmentary bullets is much higher than that of controlled expanding bullets at low impact velocities, providing the cluster has sufficient density and momentum relative to game body weights.

During TBR testing, a packet of vintage Winchester Western .30-30 160 grain hollow point ammunition was tested on medium game animals. This is perhaps the earliest example of a frangible bullet. As best as could be determined after extensive research, it could be concluded that historically, the .30-30 was possibly not standing up to its design premise and that a frangible bullet was adopted to increase wounding capacity.

The .30-30 160 grain soft point load was intended to produce wide wounding and fast kills as a result of the newly discovered powders which generated exceptionally high velocities (for 1894). This was a complete turnaround from past terminal ballistics research which had proven that the bigger the bore, the wider the wound. The .30-30 (.30 WCF) loaded with a controlled expanding bullet is not a great deal more emphatic than the .45/70, the .45/70 having already proven to be an emphatic killer. Western's hollow point load was introduced a little while after the soft point.

While the frangible .30-30 bullet would have been acceptable for use on the smaller deer species of the U.S, one has to wonder how this load fared on the Grizzly bear featured on the ammunition box of the .30-30 hollow point ammunition. The results would most likely have been disastrous. About 200 grains is a safe minimum frangible bullet weight for these body weights.

Frangible bullets are important at low velocities, especially at long ranges. A frangible bullet capable of rendering a wide wound in the absence of disproportionate to caliber wounding (high velocity) helps ensure fast bleeding for fast killing.

As a short recap, with ideal shot placement and utilizing a cartridge with sufficient power to penetrate the vitals of intended game, we can destroy the CNS and cause an instant kill - however this is often idealistic and unrealistic. With less than ideal shot placement, high velocity can initiate hydrostatic shock and hydraulic wounding to help ensure fast kills out to ordinary hunting ranges (300 yards). In the absence of high velocity, a fragmentary projectile can ensure fast killing via hydraulic shock and wide (mechanical) wounding, producing fast bleeding. In all instances, bullet weight and bullet construction need to be matched to the job at hand.

Please try to remember the following for medium game hunting:

Choose light and stout or heavy and soft.

A light but stout projectile can deliver hydrostatic shock while having the tough bullet construction needed to deliver sufficient penetration. However this has a range limitation, usually of around 300 yards, after which, careful shot placement is required. This can be counterproductive in cross winds. Nevertheless, this method is often the most effective for minimizing meat damage on lighter medium game at ordinary hunting ranges (out to 300 yards).

When chest shooting heavy game, a heavy but stout controlled expanding projectile driven as fast as the shooter can manage produces the fastest possible killing. As O'Rourke said, use enough gun.

Use enough gun. The .338 Win Mag and controlled expanding 225gr Nosler Partition can be put to great work on bear. That said, shot placement is a key factor to effect extremely fast killing.

A heavy yet soft and frangible or partially frangible projectile (loses some weight) may not deliver hydrostatic shock very far depending on game body weights, but providing the cluster is dense enough, it will be capable of rendering deep, broad and highly traumatic wounding across a wide range of body weights. Good frangible bullet designs can continue to produce mechanical wounding and a measure of hydraulic shock down to impact velocities of 1600fps with some exceptional projectiles continuing to produce excellent performance down to velocities as low as 1400fps.

For those wondering about the middle ground between light and stout and heavy and soft, there are certainly some good bullet designs on the market. One of the best middle ground bullets is the Hornady SST, a semi frangible bullet design that tries to retain some weight for penetration. A specific example is the 7mm 162 grain SST which is effective on Red/Mule deer at close ranges (adequate penetration) yet is capable of producing wide wounding at extended ranges (around 1000 yards in the 7mm Remington Magnum).

On the other hand, we do have to be a bit careful with the middle ground. For example, the Nosler Accubond has core bonding in an attempt to toughen the bullet but is also designed to be fast expanding and is generally available in mid weights such as the 140 grain .270 Winchester bullet. This particular load works extremely well on mid-sized deer at ordinary hunting ranges however, the Accubond can suffer when pushed to the extremes. It can be too stout for low velocity work yet too soft for tough game. In this regard, we have to be careful as to how we use a 'general purpose' bullet design.

You may wish to take a note from the Taoists and choose the middle ground so as to be prepared for any contingency, however if you fail to fully understand the limits of your cartridge versus your intended game, you may choose something which is neither fish nor fowl and does a generally bad job within the role you have chosen for it. For example, you may load the .375 caliber 260 grain Accubond for an African trip. And while this works exceptionally well on some larger bodied game, you might be in for a world of hurt if you try to tackle a cape buffalo with this bullet and find that it completely runs out of steam before reaching vitals. Please use my cartridge knowledge base and books to obtain a deeper understanding of how each of the manufacturers bullets work, their strengths and limitations.

I have been continuously researching wounding for most of my life and the results and variables are far greater than can be covered in one short document on effective game killing. Nevertheless a rudimentary understanding of the fundamentals of game killing, wounding and speed of killing can serve as a useful platform before continuing on and exploring my in-depth research as well as your own field observations.

Looking forwards, we seem to be heading towards some very strange extremes. In one camp, we have hunters looking for any excuse to use low powered cartridges in short barreled suppressed rifles and or AR-15 platform rifles while in the other extreme, a few gun companies continue to work towards barrel destroying ultra-velocity magnums. Either approach can cause a great deal of problems for hunters. Ultra-fast cartridges can cause shallow penetration at close ranges and ironically still lead to disappointment when bullets still display vast drop and wind drift at truly long ranges. The fastest cartridges may have a barrel life of less than 600 rounds, 200 of which may be used up during load development.

Modern low powered cartridges are simply that - low in power. You do not have to be rocket scientist to figure this out. If the bullet is the same weight as a 7.62x39 or .30-30 bullet and going at the same speed, it will produce the same results regardless of how it is labelled. To recap from earlier, the slower you go - the wider you need to go (think .45 etc) or the more the bullet needs to shed weight if we are seeking optimum killing performance. This also ties back into the problem of forcing people to use homogenous copper bullets for environmental reasons. Low power and stout bullets simply don't work that well together unless the projectile has specialized design characteristics.

If the bullet is to shed weight it may need significant weight to begin with (depending on the size animals you are hunting) in order to achieve reliable penetration. Also remember this; there is little that can be done now that has not been done before. There is no new magical cartridge that offers twice the killing power with half the energy. Projectile designs are certainly advancing in some areas however there are limitations as to how far this can be taken.

As a hunter, the primary factor that must be foremost in your mind is animal welfare, not how short or light your rifle is or whether it can handle a thirty round magazine (even if you are a culler). Factors such as recoil or cost should also be treated as secondary to the primary goal of a fast effective kill.

As far as new cartridge designs go, please try to refrain from becoming caught up in hype. The physics of wounding are really rather straight forwards once you have a full understanding of the basics. The trick is just that - to understand the basics. Once you have understood the fundamentals of game killing and how cartridges behave in general, then you can move forwards and not be misled by marketing fabrications.

Effective Game Killing - Part 2

Shot placement and vital zones

View attachment 78403

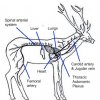

Deer vitals courtesy of my wife and lifelong research partner Steph.

The Lungs - aim here!

All of a mammal's blood must pass through the lungs where it can be released of carbon dioxide and enriched with oxygen to fuel the body. Blood leaves the heart situated below the lungs through the pulmonary artery which becomes a network of arteries feeding into the blood capillaries of the lungs. Once enriched with oxygen, the blood then travels back to the heart, then out through the aorta artery to be pumped throughout the body. Although associated with the respiratory system, destruction of the lungs is one of the fastest ways to bleed out the circulatory system ensuring a quick clean kill. On top of this the lungs present the largest, safest target for the hunter.

As viewed broadside, a deer's lungs begin at the intersection of the scapular and humerus bones of the foreleg. In height, the heaviest portions of the lungs are situated at the center of the chest, in line with the lower foreleg. The lungs reach to within an inch of the spine, which is not to be confused with the top of the fur line because above the spine, the dorsal vertebrae may extend upwards by three or more inches. At their lowest point, the lungs are again around three inches above the line of the brisket and are thinner at their extremities to accommodate the heart. Behind the foreleg the bottom of the lungs extend little more than 2 inches before tapering upwards sharply, running out to thin edges just short of the last few ribs.

Based on a White Tail deer sized animal viewed broadside, head to the right and using the straight lower leg as a center line, a shot to the center of the chest will destroy the heaviest portion of the lungs ensuring a fast bleed and therefore fast kill. A shot 3 inches above center at 12 o'clock will destroy the upper lungs, an equally fast kill. However, it is possible to strike too high between the lungs and spine or the dorsal vertebrae above causing instant collapse followed by recovery after a few seconds leading to escape and a slow kill.

Approximately two to three inches forwards of dead center (foreleg) at 3 o'clock is the ball joint intersection of the scapular and humerus bones. And from the front line of the front leg through to the ball joint intersection lies the autonomic plexus. This is a major network of nerves which when hit soundly, causes instant collapse and death. A shot in this area has the potential to destroy the autonomic plexus along with the forward portions of the lungs and locomotive muscles and bones. The autonomic plexus (sometimes called hilar zone) is the most useful aiming point for fast killing. This shot placement is also particularly useful when using cartridges that have enough bullet weight to penetrate bone but not enough velocity to initiate hydrostatic shock or extremely wide wounding.

It is important to understand that shot placement involves cultural traditions. For example, some cultures (particularly USA hunters) prefer a meat saver shot, striking the lungs behind the foreleg in an attempt to save meat. In Europe, the traditional method has been to aim forwards and although this does cause more meat destruction, this shot placement helps ensure rapid killing. Also, if you look more closely at this subject, you can see how small changes in POI may affect the hunter's perception of a cartridge. One hunter may state that X cartridge is a very fast and emphatic killer while another may call the same cartridge abysmal - each assessment based on differing traditions or habits relative to the hunter's point of aim. It is up to you to decide which method you wish to employ.

Much will depend on the power and penetrative abilities of your cartridge. Ideally, you should be aware of both points of aim and should be able to switch from one to the other depending on the individual situation. If for example you are hunting with a high velocity cartridge using soft bullets that have the potential to suffer shallow penetration, then a meat saver shot will enable adequate penetration and hydrostatic shock can be counted on for a fast kill.

On the other hand, it is very unwise to apply the meat saver shot when hunting large heavy bovines because even if you are using the likes of a .375 caliber rifle, this really is still quite a small bore diameter relative to the size of the animal you are hunting. Instead, a long heavy for caliber bullet of sound construction should be driven through the forwards portion of the chest where it can do the most damage.

As yet a further example, let's say that we are using a .308 Winchester for a wide variety of game. On very large animals it can again be good to aim to strike the forwards chest with a long and heavy bullet of sound construction in order to affect a very fast kill. I can promise you that on large African plains game, your guide will be very happy if you hunt in this manner and achieve a fast kill without any need to track your animal for minutes or hours.

Having said this, there comes a point where the size of the animal will overcome the wounding potential of our cartridge. If for example we are suddenly confronted with an angry bovine, our .308 bullet may not be enough to penetrate ball joints. By the same token, it will lack the wounding potential for a meat saver style shot. So in this example, we must look to the neck and head as our point of aim. All I wish to convey here is that while the forwards chest is an optimal point of aim, we do need to exercise some common sense.

Unfortunately, many people - including those with vast past experience, lack the confidence to aim forwards. Instead, in a halfhearted attempt to break bone, the point of aim is brought forwards to the center line of the leg but no further forwards for fear of a forwards miss. And while this point of aim can be quite sufficient, it does not produce the same instantaneous results on the likes of African game as the forwards shoulder shot, destroying tissue, bone and the autonomic plexus.

The key to the forwards shoulder shot is to use the front line of the front leg. This may sound like nit picking relative to the center line of the front leg but I can assure you that there are differences which you will discover. If the shot goes further forwards, you will still achieve a fast kill. If the shot goes to the rear, you will still achieve a clean kill via a center lung hit. If you strike true, well you will see the results for yourself.

View attachment 78404

Although slightly quartering, this photo shows the point of aim for an autonomic plexus (forwards shoulder) broad side (and slightly quartering) shot. Note that the crosshair is aligned with the front line of the leg- not the center line. Many hunters lack the confidence to aim in this manner.

If you wish to study this for yourself, you can replicate my research if you hunt with a low velocity rifle such as a .30-30 or like velocity cartridge loaded with hunting projectiles (6.5x55 with factory ammunition is another good example). If you are used to utilizing the meat saver shot, try now to utilize the autonomic plexus shot and see what happens. Note how quickly the animal drops when using the front line of the front leg as your point of aim. Once you have an understanding of just how effective this shot placement is, you will never use your low velocity cartridge as you once did.

Getting back to other areas of the lungs, a shot striking a deer around three inches low at 6 o'clock strikes the bottom of the lungs and the arteries feeding into them from the heart, a reasonably fast killing shot but if it is slightly too low the shot may severe the heart (see heart) or simply the brisket, both slow killing shots. A shot striking three to five inches to the rear of the chest at 9 o'clock from dead center is a slow killing shot unless the cartridge used has immense wounding potential.

High power cartridges may damage the rear portions of the lungs as well as rupturing the diaphragm however, animals usually run at least as far as when heart shot. The rear thin portions of the lungs, directly behind the foreleg tapering up and along the ribs, are considered a slow bleeding area and therefore a larger amount of tissue must be destroyed to effect a fast kill. High velocity cartridges such as the .270 .280 and .30-06 win out over smaller, milder calibers for fast killing in this area.

The greatest method of creating Spinal shock transfer is through shots that strike the upper half of the chest. Below center, the ribs are a long way from the spine therefore mid to low shots sometimes fail to produce shock, such as the heart shock and game may cover considerable ground after such a shot.

A true rear lung shot or 'meat saver' should be taken with the foresight or crosshair aimed snugly behind the foreleg. If the aim is taken any further back (as is common amongst inexperienced hunters these days), the shot will strike the tapered region of the lungs. The cross body meat saver shot is especially important to .22 center fire user as it allows the projectile to deliver more energy to the lungs, avoiding bullet failure on the shoulder. But again, keep shots tight! The other point of aim suited to .22 centerfire users is the soft junction between the shoulder and neck, giving access to the lungs when game are quartering on as well as the nerves and arterial system of the lower neck when broadside.

In pigs, the layout of the lungs can be very deceptive; the curvature of the spine at the shoulder is very low with the top third of the chest as viewed from the side consisting of dorsal vertebrae, cartilage and muscle to power the head. For this reason, it is important to consider the lower two thirds of the pigs shoulder as a vital zone. The lungs are completely protected by the shoulder, tapering up almost vertically at the rearmost line of the foreleg with the diaphragm positioned directly behind the foreleg. Therefore not only is the vital zone limited to the lower two thirds of the chest, but also from the foreleg forwards including the arteries and veins of the neck.

That said, a shot high (below the spine) and flush behind the shoulder will strike the rear lungs and can be a good killer but slight error may result in either a liver or a gut shot. Bear also have a 'low profile' and again, it is important to avoid making the mistake of aiming too high, striking fat, dorsal vertebrae (or just fur) while missing vitals. A high hit boar (pig or bear) can be a nightmare in that the animal will be knocked unconscious via hydrostatic shock, but is for all intents and purposes only 'sleeping'. The wound may even look thorough. Then suddenly our quarry awakens and all hell breaks loose and we seemingly become instant experts at highland dancing. This is also why I carry a good long knife!

View attachment 78405

Steph's pig anatomy 101.

Upon gutting any game animal, it is worth studying the causes of death and condition of each organ. A good lung shot will leave the chest cavity full of congealed blood; the meat will be well bled out for the table negating the necessity to bleed out the arteries of the neck.

Please note: if you are a long range shooter, more on the subject of shot placement can be found within my long range book series (Particularly Long Range Cartridges and Long Range Shooting). Techniques do vary when long range hunting and there is a great deal to consider.

The Heart

At the bottom of the chest, starting in line with the foreleg and ending three to four inches behind, lies the heart. The heart is responsible for pumping oxygen and nutrient rich blood to all parts of the body. Despite popular belief, the heart is not a good target for a fast killing shot. A heart shot without complete destruction can allow oxygen rich blood to be locked in the brain and locomotive muscles, allowing an animal to run long distances before collapsing. Shots falling low into the heart may allow some species of deer to run several hundred yards often making tracking difficult.

The Liver

Viewed broadside the liver appears roughly in the middle of an animal. The liver hangs from the spine descending roughly halfway down, between the paunch and the diaphragm. The liver is responsible for metabolizing fats, proteins and carbohydrates into the blood. It also detoxifies the blood as well as performing many other functions. The Hepatic artery and vein pass through the liver although most of the liver can be considered a fast bleeding area.

The liver is a very small target and difficult to hit deliberately and for this reason the liver should not be regarded as an aiming point. However, the liver is often hit when game step forwards as the hunter takes the shot, or are running when the shot is taken, or when angling shots are taken. If the liver is destroyed an animal may run someway (usually quite stiffly / bunched up) but will succumb quickly. Sometimes, less experienced hunters will simply divide the animal into four quarters with their scope crosshairs and pull the trigger, the result is either a fluke hit to the liver or else a wounding gut shot.

Long range hunters can make use of the liver as a secondary target however this is a subject I will not delve into here. These specialized topics are covered within my long range book series.

Directly behind the liver and attached to the spine are the kidneys, responsible for filtering waste from the blood. The kidneys are slow bleeding organs and if wounded result in a slow death.

View attachment 78403

Deer vitals courtesy of my wife and lifelong research partner Steph.

The Lungs - aim here!

All of a mammal's blood must pass through the lungs where it can be released of carbon dioxide and enriched with oxygen to fuel the body. Blood leaves the heart situated below the lungs through the pulmonary artery which becomes a network of arteries feeding into the blood capillaries of the lungs. Once enriched with oxygen, the blood then travels back to the heart, then out through the aorta artery to be pumped throughout the body. Although associated with the respiratory system, destruction of the lungs is one of the fastest ways to bleed out the circulatory system ensuring a quick clean kill. On top of this the lungs present the largest, safest target for the hunter.

As viewed broadside, a deer's lungs begin at the intersection of the scapular and humerus bones of the foreleg. In height, the heaviest portions of the lungs are situated at the center of the chest, in line with the lower foreleg. The lungs reach to within an inch of the spine, which is not to be confused with the top of the fur line because above the spine, the dorsal vertebrae may extend upwards by three or more inches. At their lowest point, the lungs are again around three inches above the line of the brisket and are thinner at their extremities to accommodate the heart. Behind the foreleg the bottom of the lungs extend little more than 2 inches before tapering upwards sharply, running out to thin edges just short of the last few ribs.

Based on a White Tail deer sized animal viewed broadside, head to the right and using the straight lower leg as a center line, a shot to the center of the chest will destroy the heaviest portion of the lungs ensuring a fast bleed and therefore fast kill. A shot 3 inches above center at 12 o'clock will destroy the upper lungs, an equally fast kill. However, it is possible to strike too high between the lungs and spine or the dorsal vertebrae above causing instant collapse followed by recovery after a few seconds leading to escape and a slow kill.

Approximately two to three inches forwards of dead center (foreleg) at 3 o'clock is the ball joint intersection of the scapular and humerus bones. And from the front line of the front leg through to the ball joint intersection lies the autonomic plexus. This is a major network of nerves which when hit soundly, causes instant collapse and death. A shot in this area has the potential to destroy the autonomic plexus along with the forward portions of the lungs and locomotive muscles and bones. The autonomic plexus (sometimes called hilar zone) is the most useful aiming point for fast killing. This shot placement is also particularly useful when using cartridges that have enough bullet weight to penetrate bone but not enough velocity to initiate hydrostatic shock or extremely wide wounding.

It is important to understand that shot placement involves cultural traditions. For example, some cultures (particularly USA hunters) prefer a meat saver shot, striking the lungs behind the foreleg in an attempt to save meat. In Europe, the traditional method has been to aim forwards and although this does cause more meat destruction, this shot placement helps ensure rapid killing. Also, if you look more closely at this subject, you can see how small changes in POI may affect the hunter's perception of a cartridge. One hunter may state that X cartridge is a very fast and emphatic killer while another may call the same cartridge abysmal - each assessment based on differing traditions or habits relative to the hunter's point of aim. It is up to you to decide which method you wish to employ.

Much will depend on the power and penetrative abilities of your cartridge. Ideally, you should be aware of both points of aim and should be able to switch from one to the other depending on the individual situation. If for example you are hunting with a high velocity cartridge using soft bullets that have the potential to suffer shallow penetration, then a meat saver shot will enable adequate penetration and hydrostatic shock can be counted on for a fast kill.

On the other hand, it is very unwise to apply the meat saver shot when hunting large heavy bovines because even if you are using the likes of a .375 caliber rifle, this really is still quite a small bore diameter relative to the size of the animal you are hunting. Instead, a long heavy for caliber bullet of sound construction should be driven through the forwards portion of the chest where it can do the most damage.

As yet a further example, let's say that we are using a .308 Winchester for a wide variety of game. On very large animals it can again be good to aim to strike the forwards chest with a long and heavy bullet of sound construction in order to affect a very fast kill. I can promise you that on large African plains game, your guide will be very happy if you hunt in this manner and achieve a fast kill without any need to track your animal for minutes or hours.

Having said this, there comes a point where the size of the animal will overcome the wounding potential of our cartridge. If for example we are suddenly confronted with an angry bovine, our .308 bullet may not be enough to penetrate ball joints. By the same token, it will lack the wounding potential for a meat saver style shot. So in this example, we must look to the neck and head as our point of aim. All I wish to convey here is that while the forwards chest is an optimal point of aim, we do need to exercise some common sense.

Unfortunately, many people - including those with vast past experience, lack the confidence to aim forwards. Instead, in a halfhearted attempt to break bone, the point of aim is brought forwards to the center line of the leg but no further forwards for fear of a forwards miss. And while this point of aim can be quite sufficient, it does not produce the same instantaneous results on the likes of African game as the forwards shoulder shot, destroying tissue, bone and the autonomic plexus.

The key to the forwards shoulder shot is to use the front line of the front leg. This may sound like nit picking relative to the center line of the front leg but I can assure you that there are differences which you will discover. If the shot goes further forwards, you will still achieve a fast kill. If the shot goes to the rear, you will still achieve a clean kill via a center lung hit. If you strike true, well you will see the results for yourself.

View attachment 78404

Although slightly quartering, this photo shows the point of aim for an autonomic plexus (forwards shoulder) broad side (and slightly quartering) shot. Note that the crosshair is aligned with the front line of the leg- not the center line. Many hunters lack the confidence to aim in this manner.

If you wish to study this for yourself, you can replicate my research if you hunt with a low velocity rifle such as a .30-30 or like velocity cartridge loaded with hunting projectiles (6.5x55 with factory ammunition is another good example). If you are used to utilizing the meat saver shot, try now to utilize the autonomic plexus shot and see what happens. Note how quickly the animal drops when using the front line of the front leg as your point of aim. Once you have an understanding of just how effective this shot placement is, you will never use your low velocity cartridge as you once did.

Getting back to other areas of the lungs, a shot striking a deer around three inches low at 6 o'clock strikes the bottom of the lungs and the arteries feeding into them from the heart, a reasonably fast killing shot but if it is slightly too low the shot may severe the heart (see heart) or simply the brisket, both slow killing shots. A shot striking three to five inches to the rear of the chest at 9 o'clock from dead center is a slow killing shot unless the cartridge used has immense wounding potential.

High power cartridges may damage the rear portions of the lungs as well as rupturing the diaphragm however, animals usually run at least as far as when heart shot. The rear thin portions of the lungs, directly behind the foreleg tapering up and along the ribs, are considered a slow bleeding area and therefore a larger amount of tissue must be destroyed to effect a fast kill. High velocity cartridges such as the .270 .280 and .30-06 win out over smaller, milder calibers for fast killing in this area.

The greatest method of creating Spinal shock transfer is through shots that strike the upper half of the chest. Below center, the ribs are a long way from the spine therefore mid to low shots sometimes fail to produce shock, such as the heart shock and game may cover considerable ground after such a shot.

A true rear lung shot or 'meat saver' should be taken with the foresight or crosshair aimed snugly behind the foreleg. If the aim is taken any further back (as is common amongst inexperienced hunters these days), the shot will strike the tapered region of the lungs. The cross body meat saver shot is especially important to .22 center fire user as it allows the projectile to deliver more energy to the lungs, avoiding bullet failure on the shoulder. But again, keep shots tight! The other point of aim suited to .22 centerfire users is the soft junction between the shoulder and neck, giving access to the lungs when game are quartering on as well as the nerves and arterial system of the lower neck when broadside.

In pigs, the layout of the lungs can be very deceptive; the curvature of the spine at the shoulder is very low with the top third of the chest as viewed from the side consisting of dorsal vertebrae, cartilage and muscle to power the head. For this reason, it is important to consider the lower two thirds of the pigs shoulder as a vital zone. The lungs are completely protected by the shoulder, tapering up almost vertically at the rearmost line of the foreleg with the diaphragm positioned directly behind the foreleg. Therefore not only is the vital zone limited to the lower two thirds of the chest, but also from the foreleg forwards including the arteries and veins of the neck.

That said, a shot high (below the spine) and flush behind the shoulder will strike the rear lungs and can be a good killer but slight error may result in either a liver or a gut shot. Bear also have a 'low profile' and again, it is important to avoid making the mistake of aiming too high, striking fat, dorsal vertebrae (or just fur) while missing vitals. A high hit boar (pig or bear) can be a nightmare in that the animal will be knocked unconscious via hydrostatic shock, but is for all intents and purposes only 'sleeping'. The wound may even look thorough. Then suddenly our quarry awakens and all hell breaks loose and we seemingly become instant experts at highland dancing. This is also why I carry a good long knife!

View attachment 78405

Steph's pig anatomy 101.

Upon gutting any game animal, it is worth studying the causes of death and condition of each organ. A good lung shot will leave the chest cavity full of congealed blood; the meat will be well bled out for the table negating the necessity to bleed out the arteries of the neck.

Please note: if you are a long range shooter, more on the subject of shot placement can be found within my long range book series (Particularly Long Range Cartridges and Long Range Shooting). Techniques do vary when long range hunting and there is a great deal to consider.

The Heart

At the bottom of the chest, starting in line with the foreleg and ending three to four inches behind, lies the heart. The heart is responsible for pumping oxygen and nutrient rich blood to all parts of the body. Despite popular belief, the heart is not a good target for a fast killing shot. A heart shot without complete destruction can allow oxygen rich blood to be locked in the brain and locomotive muscles, allowing an animal to run long distances before collapsing. Shots falling low into the heart may allow some species of deer to run several hundred yards often making tracking difficult.

The Liver

Viewed broadside the liver appears roughly in the middle of an animal. The liver hangs from the spine descending roughly halfway down, between the paunch and the diaphragm. The liver is responsible for metabolizing fats, proteins and carbohydrates into the blood. It also detoxifies the blood as well as performing many other functions. The Hepatic artery and vein pass through the liver although most of the liver can be considered a fast bleeding area.

The liver is a very small target and difficult to hit deliberately and for this reason the liver should not be regarded as an aiming point. However, the liver is often hit when game step forwards as the hunter takes the shot, or are running when the shot is taken, or when angling shots are taken. If the liver is destroyed an animal may run someway (usually quite stiffly / bunched up) but will succumb quickly. Sometimes, less experienced hunters will simply divide the animal into four quarters with their scope crosshairs and pull the trigger, the result is either a fluke hit to the liver or else a wounding gut shot.

Long range hunters can make use of the liver as a secondary target however this is a subject I will not delve into here. These specialized topics are covered within my long range book series.

Directly behind the liver and attached to the spine are the kidneys, responsible for filtering waste from the blood. The kidneys are slow bleeding organs and if wounded result in a slow death.

Effective Game Killing - Part 2

The Abdominal Cavity

The gut is a slow killing zone. Gut shots may take hours or days to kill depending on the extent of wounding. Death may be caused by infection as well as general 'blood poisoning' as a result of digestive acids passing into the blood stream. Other factors may include severe pain trauma which then eventually leads to coma after several hours. Following this, the animal may remain in a coma until its eventual death.

Visible indicators of a gut shot include a deep audible 'whock' sound as the bullet strikes and game will often rear up on hind legs before running, although it is not uncommon to see no sign of a hit at all. Potent cartridges loaded with very soft fast expanding projectiles can sometimes anchor game through the destruction of such a large amount of the gut that the body is forced into coma quickly. Beyond these exceptions, many cartridges allow game to escape leaving no blood trail and often no gut fiber trail either, leaving the animal to endure a slow painful death.

The Neck

From the lungs forwards, arteries, veins and nerves of the chest cavity taper into the neck. The vital systems of the neck includes the spine and spinal nerves, the carotid artery transporting blood to the head and the jugular vein transporting blood back to the heart. Destruction of any of these causes a fast kill and even if the spine is not hit, suitable projectiles will often transfer shock to the spine causing instant collapse. That said, during the roar or rut, the neck of a male deer can become very swollen and shots to the neck may result in flesh wounds only. This is largely due to the fact that the arteries and veins are incredibly elastic; sometimes remaining intact after the bullet has passed through the neck.

Typically, projectiles that create an explosive wound destroy both the spine and circulatory system however; it is often impractical to hunt with such loads. The neck shot should be limited to ranges for which a margin of accuracy can be guaranteed. Broadside shots are best placed to strike just below the spine which, for rifles sighted three inches high at 100 yards, means a hold on the bottom line of the neck on medium sized game at ranges of between 50 and 200 yards.

It is worth noting that in an accident where a human breaks their neck, the human may live on. In contrast to this, a rifle shot will generally completely destroy the spine, circulatory system, nerve ganglia and surrounding tissues. The damage is so severe that regardless of variations to this description and mechanisms, life simply cannot be sustained. A shot which destroys the spine (from the chest forwards) will generally cause instant coma followed by death. A shot which destroys the rear section of the spine may not cause coma / collapse (although the animal has no control over its rear extremities). If blood loss is slow, life may continue for some time, resulting in a slow kill.

The Head

There are two aspects of the nervous system. The Peripheral system refers to all of the branches of nerves throughout the body acting as sensory organs monitoring internal and external environments, responding to stimuli and conducting impulses. The central nervous system (CNS) refers to the brain and the highway of all information, the spinal cord. The destruction of the brain or spinal cord as far back as the shoulder causes instant death by simply shutting down the vital systems of the body (apart from the self-regulating heart).

Far from the ideal shot due to the accuracy required, the head shot is best suited to close ranges and for finishing wounded animals. Suitable points of aim include the ear or between the ear and eye as viewed broadside. From the front aim between the eyes if the rifle is sighted to shoot high or slightly above the eyes if the rifle is sighted dead on. Pigs are one of the toughest animals to head shoot front on because of both the shape and density of the skull.

As an example, a .308 bullet of any weight and style of construction may simply bounce of the skull. This may result in a cut and mild bruising or it can cause instant collapse with severe internal hemorrhage. It is always difficult to predict exact results. If you do shoot a pig in the head front on and the animal collapses, be sure to check the wound quickly to make sure the bullet has actually penetrated the skull. The pig may only be rendered unconscious and if this is the case, you need to bleed the animal quickly to ensure a fast and humane kill (and to bleed out the meat). This also helps prevent any impromptu incidents of highland dancing.

If head shooting game at very close ranges (inside 15 yards), you must understand that your bullet will be traveling at least 1.5 inches below the center of the crosshair on a scoped rifle due to the physical height difference between the scope and the bore below. If this is not taken into consideration, there is a severe risk of a low strike, resulting is an immensely cruel, slow killing wound. Although scopes have given us superior accuracy over open sights their added height can cause confusion for close range head shots. A simple method for close range or coup de grace shots out to 15 yards is to place the horizontal crosshair flat across the top of the head.

While certainly a fast killing shot, a lot can and does often go wrong with head shots. Jaw shots are the most common mistake and game do run long and hard with a jaw shot which can make tracking extremely difficult. A cattle beast can present us with a relatively large target area but a deer or antelope is an entirely different story. The head shot is certainly one of the least ethical points of aim.

Game at Varying Angles

The quartering away shot describes a shot taken at an animal facing partially away from the hunter. In order to destroy the lungs for a fast kill the shot may have to be placed to pass through the paunch or rear ribs. Solidly packed gut fiber or in-line ribs may be encountered as the bullet makes its journey to the lungs therefore bullet construction is a vital factor. Long for caliber bullets, offering high sectional densities and straight line penetration win out over light super explosive bullets on this shot and the more powerful of cartridges will often transfer shock to the spine, after passing through the lungs and impacting the frontal ribs of the offside.

A quartering on shot describes a shot taken at an animal partially facing the hunter. When angling shots through the front quarter into the lungs, the point of the shoulder (ball joint) is often the best place to aim. However if the animal is facing slightly more toward the hunter the point of aim can be placed on the crease between the brisket and the shoulder muscle. This shot if true will strike the main nerve centers as well as the lungs, pole axing the animal for sure.

From the front, even at close ranges, shots placed squarely in the middle of the chest can sometimes pass between and fail to destroy the lungs. A large wound channel can minimize such failure however, as a power level example, it is not uncommon for some brands of .270win factory ammunition to cause slow or unrecovered kills on animals as light as 40kg (80lb) when hit this way at close range. Where doubt exists, a more reliable result can be obtained by either aiming slightly off center or aiming higher towards the neck and spine.

Tail on Shots

Also known as the Texas heart shot, the tail on shot refers to the common occurrence when deerstalking of finding an animal facing directly away from the hunter but usually looking back towards the hunter, poised for flight. This shot is considered unethical in Europe but is from time to time regarded as acceptable in the USA Australia and NZ.

There are two distinct methods of applying the tail on shot relative to cartridge power. With lighter cartridges, one method is to angle the shot to destroy the spine and follow through quickly with a finishing shot. Another method is to use a cartridge of great power with wide wounding projectiles to completely destroy one ham, causing the femoral artery to bleed out while also employing a finishing shot to the neck or head.

With potent calibers and bullets of sound construction, it is possible to achieve full length penetration, destroying the lungs as well as the autonomic plexus causing instant poleaxe. Bullet construction is much more important than sectional density for this shot and many projectiles fail under these circumstances, even those seemingly purpose built for the job such as heavy round nosed bullets. Optimum projectiles for this task should be of a premium controlled expanding design and boast a high sectional density. The Barnes TXS and TTSX are ideal; the Nosler Partition can be useful in certain combinations (where weight and SD are very high) as well as some core bonded bullet designs.

A heavy and potent chambering can certainly achieve a fast kill with tail on shots however there is still a lot that can go wrong leading to slow and cruel kills. Furthermore, tail on shots can render a carcass un-edible after it has been fouled from end to end with gut contents. Nevertheless, there are times when you may have to take a tail on shot in order to finish a wounded animal.

Nathan Foster has a long established background in the gun industry, recognized for his extensive research and for educating and supporting hunters around the world. Nathan has taken over 7500 head of game, testing the performance of a wide range of cartridges and projectiles, and is a worldwide expert in the field of terminal ballistics. His ongoing research has been carefully recorded, analyzed and documented in his online cartridge knowledge base for the benefit of all hunters and shooters (www.ballisticstudies.com). Rifle accurizing and long range shooting are among Nathan's specialties. For many years, Nathan has provided both rifle accurizing services and a long range shooting school. Nathan is also the designer of MatchGrade bedding products and has assisted many 1000's of hunters worldwide to improve their rifle accuracy, shooting technique and hunting success. The Practical Guide to Long Range book series is one of Nathans hallmark achievements, primarily focused on fast, humane harvesting of game at long ranges.

The gut is a slow killing zone. Gut shots may take hours or days to kill depending on the extent of wounding. Death may be caused by infection as well as general 'blood poisoning' as a result of digestive acids passing into the blood stream. Other factors may include severe pain trauma which then eventually leads to coma after several hours. Following this, the animal may remain in a coma until its eventual death.

Visible indicators of a gut shot include a deep audible 'whock' sound as the bullet strikes and game will often rear up on hind legs before running, although it is not uncommon to see no sign of a hit at all. Potent cartridges loaded with very soft fast expanding projectiles can sometimes anchor game through the destruction of such a large amount of the gut that the body is forced into coma quickly. Beyond these exceptions, many cartridges allow game to escape leaving no blood trail and often no gut fiber trail either, leaving the animal to endure a slow painful death.

The Neck

From the lungs forwards, arteries, veins and nerves of the chest cavity taper into the neck. The vital systems of the neck includes the spine and spinal nerves, the carotid artery transporting blood to the head and the jugular vein transporting blood back to the heart. Destruction of any of these causes a fast kill and even if the spine is not hit, suitable projectiles will often transfer shock to the spine causing instant collapse. That said, during the roar or rut, the neck of a male deer can become very swollen and shots to the neck may result in flesh wounds only. This is largely due to the fact that the arteries and veins are incredibly elastic; sometimes remaining intact after the bullet has passed through the neck.

Typically, projectiles that create an explosive wound destroy both the spine and circulatory system however; it is often impractical to hunt with such loads. The neck shot should be limited to ranges for which a margin of accuracy can be guaranteed. Broadside shots are best placed to strike just below the spine which, for rifles sighted three inches high at 100 yards, means a hold on the bottom line of the neck on medium sized game at ranges of between 50 and 200 yards.

It is worth noting that in an accident where a human breaks their neck, the human may live on. In contrast to this, a rifle shot will generally completely destroy the spine, circulatory system, nerve ganglia and surrounding tissues. The damage is so severe that regardless of variations to this description and mechanisms, life simply cannot be sustained. A shot which destroys the spine (from the chest forwards) will generally cause instant coma followed by death. A shot which destroys the rear section of the spine may not cause coma / collapse (although the animal has no control over its rear extremities). If blood loss is slow, life may continue for some time, resulting in a slow kill.

The Head

There are two aspects of the nervous system. The Peripheral system refers to all of the branches of nerves throughout the body acting as sensory organs monitoring internal and external environments, responding to stimuli and conducting impulses. The central nervous system (CNS) refers to the brain and the highway of all information, the spinal cord. The destruction of the brain or spinal cord as far back as the shoulder causes instant death by simply shutting down the vital systems of the body (apart from the self-regulating heart).

Far from the ideal shot due to the accuracy required, the head shot is best suited to close ranges and for finishing wounded animals. Suitable points of aim include the ear or between the ear and eye as viewed broadside. From the front aim between the eyes if the rifle is sighted to shoot high or slightly above the eyes if the rifle is sighted dead on. Pigs are one of the toughest animals to head shoot front on because of both the shape and density of the skull.

As an example, a .308 bullet of any weight and style of construction may simply bounce of the skull. This may result in a cut and mild bruising or it can cause instant collapse with severe internal hemorrhage. It is always difficult to predict exact results. If you do shoot a pig in the head front on and the animal collapses, be sure to check the wound quickly to make sure the bullet has actually penetrated the skull. The pig may only be rendered unconscious and if this is the case, you need to bleed the animal quickly to ensure a fast and humane kill (and to bleed out the meat). This also helps prevent any impromptu incidents of highland dancing.

If head shooting game at very close ranges (inside 15 yards), you must understand that your bullet will be traveling at least 1.5 inches below the center of the crosshair on a scoped rifle due to the physical height difference between the scope and the bore below. If this is not taken into consideration, there is a severe risk of a low strike, resulting is an immensely cruel, slow killing wound. Although scopes have given us superior accuracy over open sights their added height can cause confusion for close range head shots. A simple method for close range or coup de grace shots out to 15 yards is to place the horizontal crosshair flat across the top of the head.

While certainly a fast killing shot, a lot can and does often go wrong with head shots. Jaw shots are the most common mistake and game do run long and hard with a jaw shot which can make tracking extremely difficult. A cattle beast can present us with a relatively large target area but a deer or antelope is an entirely different story. The head shot is certainly one of the least ethical points of aim.

Game at Varying Angles

The quartering away shot describes a shot taken at an animal facing partially away from the hunter. In order to destroy the lungs for a fast kill the shot may have to be placed to pass through the paunch or rear ribs. Solidly packed gut fiber or in-line ribs may be encountered as the bullet makes its journey to the lungs therefore bullet construction is a vital factor. Long for caliber bullets, offering high sectional densities and straight line penetration win out over light super explosive bullets on this shot and the more powerful of cartridges will often transfer shock to the spine, after passing through the lungs and impacting the frontal ribs of the offside.

A quartering on shot describes a shot taken at an animal partially facing the hunter. When angling shots through the front quarter into the lungs, the point of the shoulder (ball joint) is often the best place to aim. However if the animal is facing slightly more toward the hunter the point of aim can be placed on the crease between the brisket and the shoulder muscle. This shot if true will strike the main nerve centers as well as the lungs, pole axing the animal for sure.

From the front, even at close ranges, shots placed squarely in the middle of the chest can sometimes pass between and fail to destroy the lungs. A large wound channel can minimize such failure however, as a power level example, it is not uncommon for some brands of .270win factory ammunition to cause slow or unrecovered kills on animals as light as 40kg (80lb) when hit this way at close range. Where doubt exists, a more reliable result can be obtained by either aiming slightly off center or aiming higher towards the neck and spine.

Tail on Shots

Also known as the Texas heart shot, the tail on shot refers to the common occurrence when deerstalking of finding an animal facing directly away from the hunter but usually looking back towards the hunter, poised for flight. This shot is considered unethical in Europe but is from time to time regarded as acceptable in the USA Australia and NZ.

There are two distinct methods of applying the tail on shot relative to cartridge power. With lighter cartridges, one method is to angle the shot to destroy the spine and follow through quickly with a finishing shot. Another method is to use a cartridge of great power with wide wounding projectiles to completely destroy one ham, causing the femoral artery to bleed out while also employing a finishing shot to the neck or head.

With potent calibers and bullets of sound construction, it is possible to achieve full length penetration, destroying the lungs as well as the autonomic plexus causing instant poleaxe. Bullet construction is much more important than sectional density for this shot and many projectiles fail under these circumstances, even those seemingly purpose built for the job such as heavy round nosed bullets. Optimum projectiles for this task should be of a premium controlled expanding design and boast a high sectional density. The Barnes TXS and TTSX are ideal; the Nosler Partition can be useful in certain combinations (where weight and SD are very high) as well as some core bonded bullet designs.

A heavy and potent chambering can certainly achieve a fast kill with tail on shots however there is still a lot that can go wrong leading to slow and cruel kills. Furthermore, tail on shots can render a carcass un-edible after it has been fouled from end to end with gut contents. Nevertheless, there are times when you may have to take a tail on shot in order to finish a wounded animal.

Nathan Foster has a long established background in the gun industry, recognized for his extensive research and for educating and supporting hunters around the world. Nathan has taken over 7500 head of game, testing the performance of a wide range of cartridges and projectiles, and is a worldwide expert in the field of terminal ballistics. His ongoing research has been carefully recorded, analyzed and documented in his online cartridge knowledge base for the benefit of all hunters and shooters (www.ballisticstudies.com). Rifle accurizing and long range shooting are among Nathan's specialties. For many years, Nathan has provided both rifle accurizing services and a long range shooting school. Nathan is also the designer of MatchGrade bedding products and has assisted many 1000's of hunters worldwide to improve their rifle accuracy, shooting technique and hunting success. The Practical Guide to Long Range book series is one of Nathans hallmark achievements, primarily focused on fast, humane harvesting of game at long ranges.